Peace Full Middle East- Jerusalem Conflict

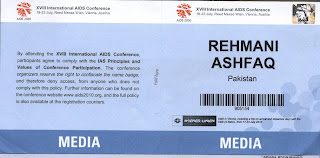

Column by: Ashfaq Rehmani

Email: pasrurmedia@hotmail.com

John L. Esposito’s book, The Islamic Threat: Myth or Reality, states the question, is Islam a threat to the West? He tells us that the answer lies in the West’s views. He says that if the Western powers continue to defend the unjust status of the Middle East in the name of an illusory or fleeting stability, Islam will be a threat. "But if the Western powers begin to appreciate the legitimacy of grievances in the Middle East, the West and Islamic movements will get along peacefully"

There have been many conflicts in the in Middle East since the time of the ancient Near East up until modern times. From Ancient Egypt conflicts Battle of Kadesh, to Modern conflicts like World War I - II, Arab-Israeli conflict, Jordan-Syria tensions, Black September in Jordan, North Yemen Civil War, the Cyprus dispute, Lebanese civil war, Libya-Egypt conflict Iraq-Kuwait clashes, Iran–Iraq War, Gulf War and aftermath, Iraq War, Fattah al-Islam and Nahr al-Bared, 9/11, Indo-Pak Crises, Pak, Iran and India Pipeline Issue. I would like to share very much important “The Israeli-Palestinian conflict” or Arab-Israeli conflict, or whatever name it goes by, is perhaps one of the more sensitive issues that are discussed. From the historic British dominance in the Middle East, and the more recent US influence and control over the region, the Anglo-American goal is simply to be able to dominate the Middle East due to the vast oil reserves and the West's economic dependence upon it. Prior to the discovery of oil, one of the main reasons for involvement in the Middle East had been religious (Christianity, Judaism and Islam all have roots in the Middle East) and on the natural arable land. During the Cold War, the Soviet excuse may have been used on numerous occasions to justify involvement there, but in modern times, it has always been for oil. Hence, the support for the Jewish people and the state of Israel has been due to the interests of oil and to ensure an ally is there in the region.

It is also no surprise that some other nations in the Middle East are also amongst the largest recipients of US military aid, like Turkey and Egypt. What makes this a particularly sensitive issue oftentimes, is due to the horrendous suffering the Jewish people suffered in (Christian) Europe during World War II, to the extent that (in the United States, anyway), any criticism of Israeli policies towards the Palestinian people and other Arabs, lends well to an automatic, unfavorable label of anti-Semitic. In the United States as well, the Jewish community is well established and has influence over many aspects of US foreign policy in the Middle East. In fact, some commentators suggest that US Zionism is more extreme that that seen in Israel itself.

Sure, the Jewish people suffered terribly during World War II and there is no one (apart from ultra Right Wing neo-Nazi types) that would deny that. However, that can also not be a reason not to criticize Israeli actions where warranted. Hence, this part of the globalissues.org web site provides a look at the on-going conflict in light of the fact that mainstream media (in the US and UK particularly) has been fairly one-sided. This is not some sort of anti-Jewish or anti-Israel sentiment, rather, a look at some of the issues from additional wider perspectives. In this section, you will find many links to a variety of resources from those critical of Israeli leadership and American policy including resources from American Jews, and others, prominent in political discourse of foreign policies.

However, it’s very much important to discus that the clash between the West and Islam will be vital to the course of world events over the coming decades. Islam is, in fact, the only civilization which ever put the survival of the West in doubt - and more than once! What is interesting is how this conflict flows not simply from the differences between the two civilizations, but more importantly from their similarities. It is said that people who are too much alike cannot easily live together, and the same goes for cultures as well. Both Islam and Christianity (which serves as culturally uniting factor for the West) is absolutist, monotheistic religions. Both are universal, in the sense of making claims to apply to all of humanity rather than a single race or tribe. Both are missionary in nature, having long made it a theological duty to seek out and convert nonbelievers. Both the Jihad and the Crusades are political manifestations of these religious attitudes, and both parallel each other closely. But this doesn't entirely explain why Islam has had so many problems with all of its neighbors, not just the West. In all these places, the relations between Muslims and peoples of other civilizations - Catholic, Protestant, Orthodox, Hindu, Chinese, and Buddhist, Jewish - have been generally antagonistic; most of these relations have been violent at some point in the past; many have been violent in the 1990s. Wherever one looks along the perimeter of Islam, Muslims have problems living peaceably with their neighbors. ...Muslims make up about one-fifth of the world's population but in the 1990s they have been far more involved in inter group violence than the people of any other civilizations. (Huntington p. 256)

Several reasons have been offered as to why there is so much violence associated with Islamic nations. One common suggestion is that the violence is a result of Western imperialism. Current political divisions among the countries are artificial European creations. Moreover, there is still lingering resentment among Muslims for what their religion and their lands had to endure under colonial rule. It may be true that those factors have played a role, but they are inadequate as a full explanation, because they fail to offer any insight into why there is such strife between Muslim majorities and non-Western, non-Muslim minorities (like in the Sudan) or between Muslim minorities and non-Western, non-Muslim majorities (like in India). There are, fortunately, other alternatives.

Crises in the Middle East are seen and interpreted differently depending on whom you ask. For example, Israel's perception of and reaction to Hamas and Hizbullah is colored by the historical trauma that the Jewish people suffered over the centuries. Unfolding events there are perceived as part of the struggle against anti-Semitism, which continues to form an integral part of the Israeli contemporary worldview. Another example of diverging interpretation would be the Muslim tendency to view conflicts through a dualistic worldview. In Muslim circles, and since the 1970s, tensions in the world have often been described as conflicts between the "arrogant ones" and the "disrespected ones". For some Muslim extremists in the 1970s and 1980s the United States and the USSR were arrogant devils, or even "the great Satan".

When the interpretive narratives between conflicting parties are so different, communication – and ultimately the resolution of conflict – suffers as a result. A huge part of one's cognitive universe is shaped by narratives – the stories told in one's family, among friends, in a history class lesson. These narratives constitute the "historiography" of the group, nation, religious community, or whatever circles the individual belongs to. History is always a selection of what is regarded as significant. Furthermore, very few historical events are preserved unless they relate to a group's identity. This has to do with belonging, identity and the "us" and "them". The narratives of what has happened to "us" in the past affect our perception of events today. To us, these stories are true in the sense that they are formed by historical fact, and are seen as especially significant because they are perceived as having happened to "us", even if we were not born at that time. "They" – people in the past – have become "us"; in illo tempore – "at that time" has become "now". This phenomenon to appropriate our ancestor's history as our own is especially pertinent to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. I recently read a short book on Palestinian history written for youth. The book conveyed historical facts, but its main purpose was to create a feeling of belonging, the idea that "this is our history". Lacking were the narratives of "the other". Facts seen as significant in Jewish history were not there. Likewise, in Israeli historiography the Palestinian narrative of "the other" is also very much absent. The "us" feeling is strengthened by ritual commemoration. Young Jewish people, born decades after World War II visit concentration camps. They experience a sense of belonging and feel that the Holocaust happened to "them".

In Palestinian history, the nakba, or catastrophe has a similar function: the trauma of those who were driven from their homes belongs to all Palestinians. Similarly, in Shi'a Islam, we know of the enormous role played by the commemoration of the Karbala tragedy (more than 13 centuries ago). Alternatively, the story of the martyrdom of Prophet Muhammad's grandson, Hussein, functions as an interpretation of the tragedies in Iraq today. So, what can be done to address these disparate perceptions of history? First, in order to promote peace and good relations, it is necessary to be aware of and interested in the narratives of the "other". A healthy mental exercise in this respect is to identify the perception patterns in one's own brain, and then see if events could be seen through other interpretations. Then we search for commonalities shared in past narratives, and act to reclaim them. We can see that dynamic present in the Barcelona Process – a reconciliation project between the 26 countries of the Mediterranean – which was inspired by Andalusia history when there was peaceful co-existence between Muslims, Jews, and Christians under Arab rule for eight centuries. And perhaps most important is making an effort to foster new narratives through mutual endeavors. We can see this played out in the story of conductor Daniel Barenboim's friendship with Edward Said, and their co-founding of the West-Eastern Divan Orchestra, a symphony orchestra comprised of young Arab and Israeli musicians. Hearing stories about what different groups have achieved together can create new patterns of perception and interpretation. Such cooperative narratives are alive and functioning today, and remain a vital part of peacemaking.

Saturday, June 26, 2010

Wednesday, June 16, 2010

Monday, June 14, 2010

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)